|

It takes a

while to download this page due to all the photos - but it´s

worth waiting for! |

When

most people think of Spain, the symbol they associate most with

the country is the fighting bull. But there is another animal that

has been of far greater importance to the Iberians throughout the

centuries – the horse. When

most people think of Spain, the symbol they associate most with

the country is the fighting bull. But there is another animal that

has been of far greater importance to the Iberians throughout the

centuries – the horse.

By

Andrea Taylor

Photographs by Ricardo Delgado

Andrea Taylor at the

Real Feria in Seville |

As in all civilisations, the horse has been employed for centuries as a weapon of war, a means

of transport and work, and for sport. The most characteristic of

Spain’s horses is the Pure Spanish Thoroughbred, or Andalusian. They

date back in origin to the very first wild horses tamed by the Iberians,

and legend claims that they are directly descended from the mythical

flying horse, Pegasus. They were left to run free until the Roman

invasion of 200BC, when they were tamed for breeding, but after the

Romans retreated, they were left to run wild again

Fighting the Moors taught Spaniards the importance of producing good

horses, but not until 1571 did Phillip II found the first Royal Stud

farm, at Córdoba. Babieca, the legendary horse that carried El Cid

across the battlefields, was an Andalusian, as were the horses ridden on

the New World expeditions by the Spanish Conqueror Hernán Cortés,

which were mistaken by the indigenous natives for gods. Many European

Kings and leaders chose this breed for their courage, speed and

temperament, and the Natural History museum of Paris still exhibits the

skeleton of a notorious Andalusian horse once ridden to victory by

Napoleon.

Doma Campera, or Andalusian Dressage,

is the style of riding favoured throughout Spain and Portugal, and

exhibitions and competitions are held frequently. Nowhere is it seen to

better advantage than during the yearly town fairs in Andalusia, where

hundreds of beautiful horses ridden by elegant women and men wearing the

traditional traje corto, some

of the men carrying women behind them clad in the finery of their

flamenco dresses, parade through the fairground providing an

unforgettable spectacle of tradition and colour. There are carriages,

too, pulled by teams of up to four pairs of perfectly matched animals

and driven by coachmen in outfits derived from those worn by the

Andalusian bandits in the 19th century. During the major fairs such as

Seville, Ronda, or Jerez, special competitions are held to test the

skill of the drivers.

|

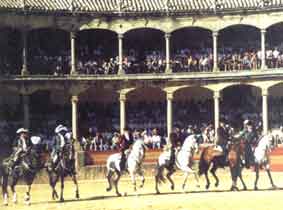

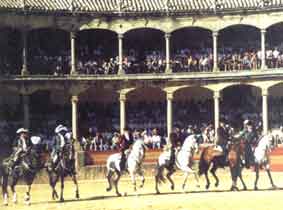

Rejoneadores in the

bullring of Ronda.

|

Horses are

also a major part of the romerías or pilgrimages which taken place

all over Spain, the most famous being that of El Rocío where thousands

of pilgrims on foot, on horseback or in ox-drawn wagons join together

for a week of singing and dancing before they reach their destination.

The horse does, naturally, also have many connections to the fighting

bull throughout Spain and Portugal, and not only for use in the ring by

the picadors as many people might imagine. The horse is used on bull

breeding ranches for inspecting and herding the cattle, and for the

testing of young bulls in the ritual known as acoso y derribo where calves are pursued on horseback by herdsmen

armed with long poles. The young bull is knocked to the ground several

times to test his strength and reaction and it is in this way that the

preliminary selection is made of the animals which will go on to be

faced by top matadors all over the peninsula.

Finally, we

come to the rejoneo, or

bullfights on horseback. Many people outside of Spain do not even

realise that it exists, when in fact, it is the pure original form of

the modern Spanish bullfight. From early times, young noblemen would go

out on horseback to hunt the wild bulls, which populated the forests and

plains of Iberia. Some historians even claim that Julius Caesar once

killed a bull from horseback in the province of Seville. Over the years,

it evolved into a more ritual, organised public spectacle and was held

in town squares all over the peninsula. In the 16th Century, Francisco

Romero is credited with being the first person to fight a bull on foot,

and from then on, rejoneo

became unfashionable, while the ”new style” of bullfighting that

most people regard as traditional rapidly spread throughout Spain. Rejoneo today is still practiced more or less in it’s original

form, and is enjoying a new wave of popularity. Many rejoneadores still come from rich or noble families, for it is a

time consuming and expensive hobby for all but the chosen few who reach

the

top. It is still the main type of bullfight in Portugal,

where the riders wear the elaborate embroidered silk coats and plumed

hats of 17th century noblemen. In Spain, they wear the typical

Andalusian country traje corto

of wide-brimmed hat, short jacket, boots, and tight split-legged

trousers protected by zahones,

wide, heavily decorated leather chaps. It is a beautiful and daring

spectacle and the horses, usually Andalusian or Portuguese thoroughbreds,

are some of the finest in Iberia.

It takes many years to prepare a horse for the ring, from

the first moments of their contact in the countryside with the wild

bulls, to the complicated and highly disciplined movements of the doma

campera. Basic training can take up to 6 years, but it may take many

more for the rider and horse to acquire the mutual knowledge and almost

telepathic communication that makes it possible for them to execute the

beautiful, precise and daring movements needed in the bullring.

A good horse

can make or break a career. Pablo Hermoso de Mendoza, now Spain’s

highest paid rejoneador was

practically unknown until a few years ago, when he purchased for the sum

of 200,000 pesetas, a black Portuguese horse rejected by it’s former

owner as useless. He named it Cagancho, after a famous Spanish

bullfighter, and within a few years he was at the top of his

profession.

Anybody who believes that horses must be forced to

participate in the spectacle should go and see Cagancho. Now known and

loved all over the peninsula, he clearly enjoys every minute of the

fights and has become a greater showman than his master. Pablo Hermoso

has been offered blank cheques for this amazing horse, but Cagancho, his

greatest asset and possible his closest friend, is priceless.

(Left): (Left):

Marcial Lalanda and Conchita Cintrón in the bullring of Cádiz 1950.

Cintrón took

the bullfight world by storm during the 30’s

and 40’s.

(Right): "Morí de Pepe Hillo" by Francisco

Goya, from his "Tauromaquia".

|

|

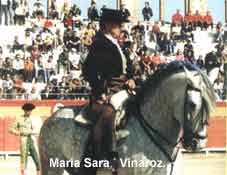

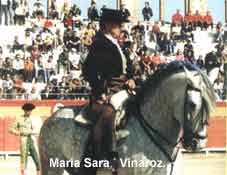

Women are

accepted far more in the world of rejoneo

than in bullfighting on foot. Maria Sara, a Parisian, is perhaps the

best of the current contenders, but she cannot compare to the most

famous female rejoneador of

all time, Conchita Cintrón, a Peruvian girl who took the bullfight

world by storm during the 30’s and 40’s.

Today the order and ritual of the rejoneo

is basically unchanged, but there are different styles of fighting.

Purists favour the cool, classical style of Javier Buendía and Fermín Bohórquez, closely resembling

the riding of the traditional Andalusian herdsmen. Other, younger riders

are developing a more spectacular style, in which their horses dance in

time to the pasodoble, execute

split second changes of direction, or perform whirlwind pirouettes in

the face of the bull.

Gines Cartagena, once Spain’s junior dressage

champion, was a master of the new style, and before his death in a

mysterious road accident 3 years ago, had been number one for several

seasons. Now, his nephew Andy, who made his debut aged just 14, is

trying to carry on the family tradition. ”My uncle taught me a great deal,” he said recently ”but his horses are still

teaching me today.”

Perhaps you may have the chance to see these fabulous, noble, rather

arrogant animals prancing in the afternoon sunshine across a ring of

golden sand one day. For me, they embody the spirit of the country. Spain may be called, because of the shape of it’s map, ”The Bullskin”, but

undoubtedly, it’s very

heart contains more than a little of the horse.

Pablo Hermoso

and Cagancho in the Maestranza, Seville. |

Pablo Hermoso de Mendoza. |

Gines Cartagena. |

|

Andy Cartagena

and his "al violín" in the Ronda bullring.

|

|

Pablo Hermoso de Mendoza in

Seville - Photo: Ricardo Delgado.

Back to FiB Kulturfront

Tauromaquia

|

(Left):

(Left):